Making art inside delicious darkness

An argument for not knowing your metrics versus knowing them.

Hello my writer friends, and happy Wednesday.

Last week, there was a comment posted to Notes by the writer

that engaged a lot of people:This is what I responded to Ashe’s note:

Yes to all of what Ashe says below, and also— as long as you’re not posting hateful content, you should take the same “me first” attitude to all your social media (“me first” as in, this is my life, my pleasure, this pleases me and brings me joy). Trends change so quickly, they’re really not worth following unless you want to be on a hamster wheel next to a dirty bowl of water your entire life.

I have never looked at my demographics here at Substack. I don’t know where people are coming from to find my newsletter, I don’t know who is unsubscribing or why, I stay in the delicious dark and just keep on putting out the content that makes me feel connected to myself and to other people and writers. Works for me— for the people that it doesn’t work for, there’s a handy “unsubscribe” button here on Substack, and “unfollow” elsewhere.

Not a problem! I’ll just stay here in my lane, top down, and old mix tape in the ancient cassette player, vroom vroom.

People got excited by the idea of creating art in “the delicious dark” so I thought I’d expound on what I meant by that.

I should begin by noting that I am a person who is aware of trends, and I used to be the kind of person who worked hard to follow them. In middle school, I begged my mother for the Sebago docksides all the cool kids were wearing; I yearned to get my thin and frizzy hair to resemble the smooth, thick ponytails of the young beauties that I envied; I wore two Swatches on my wrist like the popular set did. Something that I learned then—that I know to be true still— is that following trends is exhausting, and can make you feel icky and untrue to yourself.

It was around high school where I learned to abandon trends and start following my gut, a direction that would serve me as a writer.

But before I became a writer, I worked as a trend forecaster. This is a part of my professional CV that I don’t think is well known: I worked in Paris, France for years at two different trend forecasting agencies.

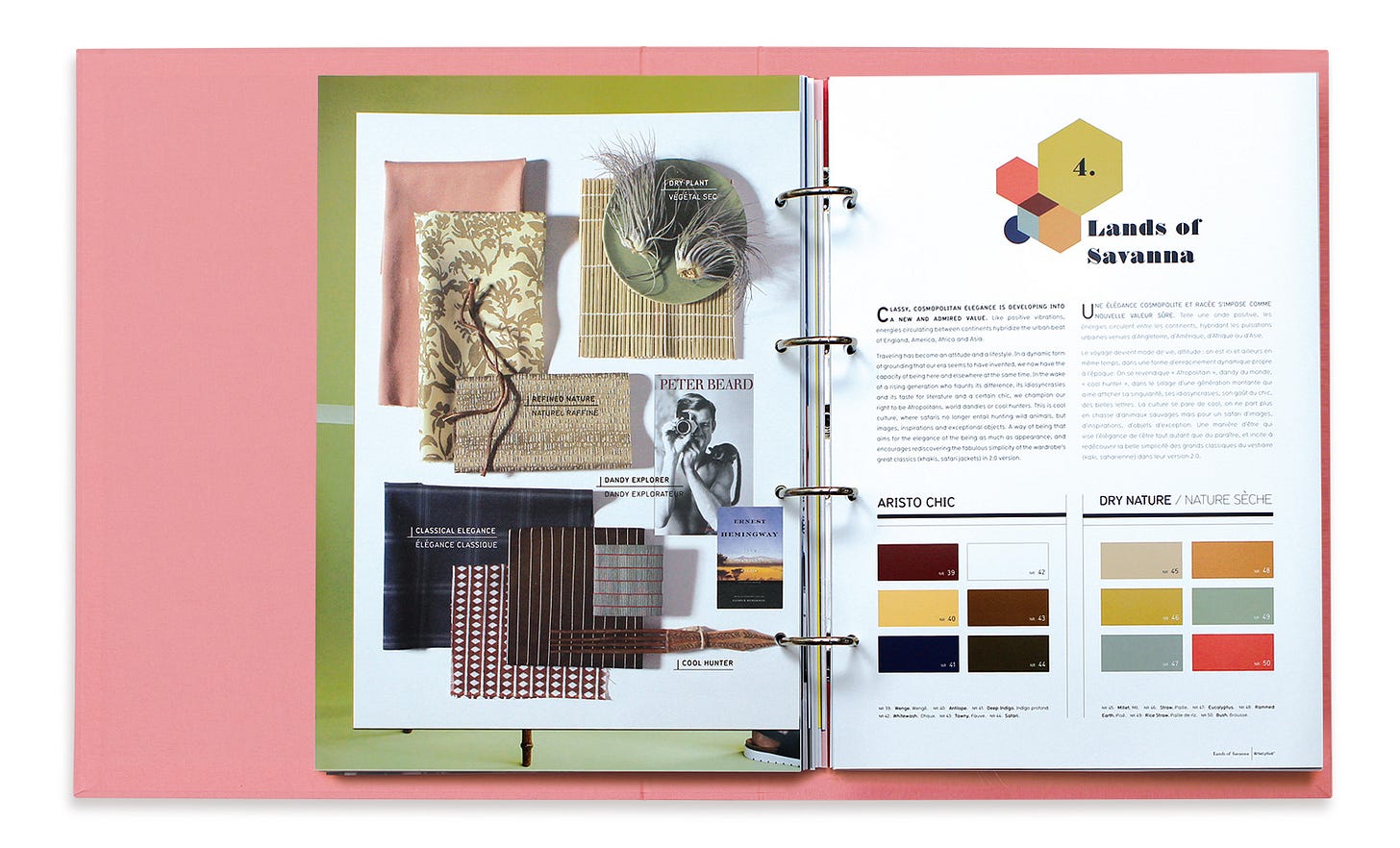

My first job was working as a French-to-English translator at the Nelly Rodi agency in Paris where I was tasked with translating the massive (and very pricey) trend books they sold to clients every season to display the textures, color schemes and reigning emotions that would inspire home goods over the coming year. Because I spoke English and French fluently, the agency brought me to huge conferences to help them sell the books. After a full day on my feet pitching the desert hues of “dry nature” and the old money hues of “aristo chic,” I would return home by train positively buzzing. Beyond just translating the company’s insights, it was dawning on me that I had a penchant for trend forecasting itself—a penchant and a passion. Given that I worked as a translator primarily, I didn’t have access to the data the researchers were using to compile these big trend books; I only had access to the final product.

But when I moved from Nelly Rodi to a smaller agency I’m going to call The Magic Box, I became immersed in a world where data didn’t matter— a world of champagne-drinking, oyster-opening savants who knew what was coming ten years down the road by sheer instinct alone. I’m not using the agency’s real name here because I doubt they would appreciate me sharing that they worked mainly off of “vibes,” but that admission is a compliment. The people that I met at Magic Box—and worked with—were old-school trend forecasters; sorcerers, really, people who could enter a crowded train station and take the pulse of what designers would be sending down the runway in five years just by observing the way that people dressed.

The agency itself was an unholy mess. There was no HR department, no established hierarchy, people were always drinking during work hours and the deadlines were last minute. More often than not, my salary was paid in haute couture instead of Euros. But I loved the work with all my heart. You see, at Magic Box, we specialized in predicting trends for the cosmetic and skin care industry. Given how intimate the products are that come out of these realms, and how sensitive and specific one’s relationship to texture and fragrance is, the work we did was truly sensual. I don’t think I looked at a data set the entire time I worked there. Instead, we would sit down with a problem such as: the ozone layer is only getting weaker. What kind of sensation and application methods will people desire 20 years down the road when the only way they’ll be able to leave their homes is in a second skin?

I eventually had to leave Magic Box because I could not pay my rent with the beautiful coats and scarves the owner insisted on paying me with instead of cash. But I took the lessons I’d learned from trend forecasting into the work that would occupy me over the next decade as a copywriter and a namer, and of course, I applied these same lessons into the things that I was writing creatively for myself.

As a copywriter, I was trained to hit certain marks tonally and from a brand standpoint. I was there to sell something, to move units, to raise the bottom line. But in my own creative writing, (probably as a response to the “on demand” commissions that I labored under) I wrote from and toward a place of total darkness. I wrote what I wanted because I wanted to. I wrote for myself to discover myself. Without an MFA or any formal education in writing, I wrote clueless about the publishing industry and blissfully naive, and it is the great project of my life to help writers return to a place of innocence where they can create meaningful and joyful work from.

Working from the delicious darkness is hard to do when you know as much about the publishing industry as I do, when you are literally the author of a guidebook about book deals. But I can tell you in all honestly that the times I’ve written under the halogen lights of analytics and trends are the times I’ve written miserably, felt miserably, and had miserable results.

I do think you need to know some things about the industry to get ahead—that’s the reason I write this Substack, and it’s the reason that I wrote the book this Substack is named for—but the most important thing that you can do as a writer is understanding why you—as a reader—read.

Generally, most people read to be taken on a journey, a journey they can relate to or be inspired by. When you read, you understand the difference between storytelling-as-monologue and storytelling-as-connection: it’s the latter form of storytelling that grabs your very heart. Once you’ve read enough books to understand the difference between these two forms of storytelling (one is selfish and/or cathartic; the other is vulnerable and forgiving) that’s when you can go back to the delicious dark and write the thing your heart is begging you to complete.