Narrative arcs and happy endings: are they a "must" in memoir?

An update on the memoir book proposal I've been working on with @thevelvetspur

Hello my writing friends!

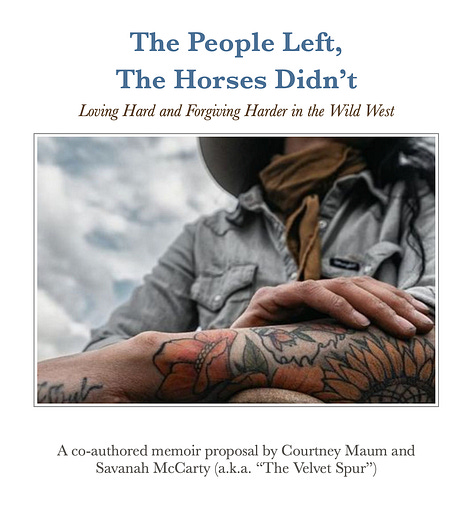

If you are new here, this section of my Substack— “Book Building with Savanah”—celebrates a memoir project I’ve been helping the horse trainer, social entrepreneur and traumatic brain injury survivor Savanah McCarty (@thevelvetspur on Instagram) to get off the ground. You can read about the origin of our collaboration here, but basically, I agreed to help Savanah develop a book proposal for a memoir about the significant challenges she’s experienced called “The People Left, The Horses Didn’t: Loving Hard and Forgiving Harder in the Wild West.”

On this Substack, I’ve posted about the nuances of Savanah’s personal mission and what led Savanah to it (using equine assisted learning to help people— especially children who have gone through trauma—build confidence, find joy, and start healing) but suffice it to say that the incidents that led Savanah to horse work and to healing were rough as hell. Since striking out on her own after high school, she’s had an actual roller coaster ride of highs and lows, and I knew—as I was conducting the interviews to put the proposal together—that I was going to have to level out those fluctuations because when there are too many ups and downs in a narrative, it can be disheartening and disorientating for a reader, especially in memoir where we generally want to root for our narrator to win/overcome/survive.

But the challenging thing about memoir writing is that memoir comes from truth. Certainly, you can curate your lived experiences to reflect the “lesson” or “vibe” you want to impart, but most memoir writers want their whole truth on the page and I know from personal experience that it feels wrong and almost unholy to not show the whole picture.

In the proposal that I handed in to my literary agency, United Talent, before the close of 2023, I tried to commercialize Savanah’s story with an overall arc and quest that also honors the fact that she doesn’t have everything figured out yet and still has a significant challenges in front of her, especially as she’s actively trying to stay sober and afloat in an extremely volatile (and expensive) industry where hay costs more than gas.

Before I share what my literary agency had to say about the project, I want to make a few things clear in order to put the verdict in a framework. When I kicked things off with Savanah in April of 2023, I agreed to work on the project for free, and we stipulated that if the book sold on proposal, I would take my fee for developing the proposal off the book advance.

Writing a proposal on spec was a significant risk for me: if the book didn’t sell based off the proposal, I would not be compensated for the time that I spent conducting interviews with Savanah to gather her life story, the time I spent in Montana working alongside her, and the months I put into writing the full book proposal, itself.

Also, working on spec meant that we had to shoot for a Big Five book deal, or at least a big advance. Why? It’s about math.

Independent publishers, academic presses and micro presses often give book advances well under ten thousand dollars. Generally, when/if I work with someone on a book proposal, 10K is the minimum flat rate I charge for the research, development and writing of the book proposal.1 So if we nabbed a ten thousand-dollar book deal, once I recouped my proposal fee, gave the commission to my agent and paid taxes, there would be no money left for me to actually write the book, nor would there be money left to compensate Savanah for her life story and her time spent on this project. So an Indie book deal wouldn’t work. When I forecasted what would work, I felt we needed a book advance of at least 150K which would allow me to reimburse myself for the proposal writing, would give me a minimum of 60K to actually write the book over the next year(s), properly compensate my agent and leave Savanah with real money for her participation and life story. This means that we needed a Big Five publishing deal.

In addition to Savanah having a turbulent life story, at the time we handed in the book proposal, there wasn’t a happy ending to the book. Savanah wants stability both financial and emotional: but instead she’s embroiled in a lawsuit with a former landowner who illegally evicted her from her Montana ranch and is costing her a fortune in legal fees, and additionally she owes beyond a million dollars for the Life Flight and respective surgeries associated with a traumatic brain injury she experienced at her place of work. Savanah would like a family but has had a suite of heartbreaks on the dating front and suffered a devastating miscarriage during the massive Bozeman flood of 2022. On the horse front, she had to sell her beloved equine partner, Sparkles, to keep her life afloat. And on, and on, and on. I thought it would be provocative and empowering to end the book with the admission that there is not a happy ending to her current story—that Savanah’s life, like all lives—is a work in progress. That as the survivor of abuse, neglect and trauma, her Hallmark ending doesn’t look like an “ending” at all—it’s a perpetual beginning, or a re-beginning, in Savanah’s case.

The book proposal for THE PEOPLE LEFT was read by my agent and another trusted colleague of hers at United Talent whom my agent, Rebecca, brought in because the other agent is an equestrian, and Rebecca wanted her point of view on the ranching aspects of the book.

They were both blown away by Savanah’s story, by her resilience, her bravery, her expertise in horsemanship and the courage it took to share her full life on the page. They found the proposal exceptionally well written and attractive (I did the proposal in Pages with lots of photo inserts and careful graphic design). But the verdict? The story didn’t have the time-honored “uplifting” arc and near tangible psychological growth that could net us a Big Five book deal.

According to the agents, there were still too many ups and downs in Savanah’s journey to fit the parameters of what makes a “commercial” book. They felt the open-ended ending wasn’t satisfying—that we needed something to go right for the heroine who had suffered so very much. (When I told Savanah this, in her typical self-effacing style, she quipped, “I’d sure as shit like something to go right for me, too!”)

I want to stand up for my agent here—or agents in this case. It hurts to hear that your story needs a happy ending, or that your story is too dark, that your life has been too hard. Absolutely, that bites. But I want to reiterate that my agent works with me as a business partner. She knows, financially and in terms of my limited time, that if I’m going to write a book for someone else, I need to be compensated correctly for my involvement. Writing the book proposal on spec and possibly never being paid for it is something I can live with—it will be worth it to have helped Savanah understand how to mold her story for an outside audience, and to have gotten to know her and the incredible energy and initiatives that she is putting out there in the world. But the writing of the book itself is an investment of multiple years, and for that, we needed a Big Five Book deal that my agent didn’t feel the current proposal was positioned to receive.

Before I move on to the options that are before us now, I want to celebrate and thank those of you who donated to the Savanah project to help me conduct the interviews and to get the proposal rolling. Both Savanah and I are moved and grateful by your faith in us. So many of you really want this story out, and we are going to get there! We just need to wrap our heads around the different directions available to us now, which I’m going to spell out here.

Gatekeepers think the current memoir proposal won’t net us a Big Five Book deal—so what now?

Option 1) Tell my agent to “submit the proposal regardless” and see what the Big 5 editors say

To my agent’s credit, she told me that if I didn’t agree with her assessment (the proposal needs a smoother, simpler arc and a happy ending) that she would submit it to Big Five editors anyway on my behalf. The problem is that I feel my agent is right in her assessment, and also, I’m hoping to submit a novel of mine to the Big Fives this year, so I really can’t afford—on a career level—to garner any passes from publishers whom I want to say ‘yes’ to my own novel in 2024.

Option 2) Smooth the arc, “Happify” the ending.

Neither I nor Savanah are excited by this option. It’s not true to her story, it isn’t true to who she is, and also, her candidness about her struggles and the goals she hasn’t reached yet is one of the reasons she has 27K+ followers on Instagram, where she is funny and also heartfelt about her life and brain trauma recovery, especially in her IG Stories.

Option 2 requires patience. The “Happy Ending” that uplifts readers could be just around the bend. Savanah is currently enjoying a new work opportunity in Tennessee with the mental health activist Miles Adcox, so the satisfying ending that would balance out the darkness of the book and help us mold the content toward a Big 5 appropriate lesson or takeaway could be coming ‘round the mountain. So this option is a possibility. But we need time to wait things out.

Option 3) Go to smaller presses [Indies, micro presses, academic presses]

Smaller presses will be more open to the rawness of this book, to a storyline that doesn’t end wrapped in a bright bow. But as I mentioned above, I can’t cover my time writing the book and pay agent commissions and taxes and compensate Savanah on a small press advance. So either I need to suddenly become independently wealthy or we need an investor willing to help cover costs that a small press book advance can’t.

Option 4) Reimagine the memoir as a memoir-in-essays

I’m always telling this to writing clients—the messier and more colorful and more traumatic your life has been, the more your story probably lends itself to a memoir-in-essays.

Take “Brutalities” by Margo Steine, for example2. Margo Steine has had such a wild life— and a violent life at that—with so many twists and turns and wild jobs (high rise welder! Teenage dominatrix!) that written as a straight memoir, the book just wouldn’t work. As a series of lyrical essays? It works extremely well.

Same thing goes for “Leaving isn’t the Hardest Thing” by Lauren Hough. Lauren was born into a sex cult over in Germany. Then she was a closeted lesbian in a Catholic school in a rural American town. Then she was a closeted lesbian in a military. Then she was a “cable guy”— her life is one wild ride after the next. Similarly to BRUTALITIES, I think that Hough’s memoir would have been very hard to pull off as a classic memoir with a beginning, middle and an end. But as a memoir-in-essays, where we can contemplate each phase of her life as its own section, and then make the links between the phases organically? It works.

Savanah’s life story has a solid thru line and her passion and mission hasn’t wavered since she was six years old. This—along with its adaptability for the silver screen given the current craze for all things Western—led me to believe that we had a good shot at a book deal for a traditional memoir with a Big Five publisher. And I still believe this.

Transforming this book proposal into an artier memoir-in-essays is a solid possibility, but in my opinion, memoirs-in-essays function better when they are sold as a completed project, rather than a proposal. And again (this is making me feel raunchy to keep harping on the money thing, but groceries and heating and having a child are expensive) I can’t write a complete manuscript on spec.

Option 5) Nab Savanah some big profiles and get the editors to come to us

Done in the right way with the right outlet, this path is a viable one. Getting Savanah a profile in Cowgirl Magazine, Sports Illustrated, The New Yorker, The New York Times or other high profile places or podcasts could see Big Five editors coming to us instead of the other way around, and then we could bend the memoir proposal toward these editors’ desires. The problem with Option 5 is that ethically, I can’t be the one to pitch these profiles because I stand to profit from them. If anyone wants to flex their pitching and profiling prowess to try and land a story on Savanah or is interested in featuring her in a newsletter of their own, please do get in touch.3

Option 6) Reposition the book as a novel

This is exciting territory, and already I have ideas about how to turn Savanah’s story into a line of incredible books for the YA+ market. We’re still thinking about this one.

By way of a conclusion…

What all this boils down to is: patience and faith that time will show us the way forward. I’m sharing all this in great detail— in greater detail than I’m comfortable with, honestly!—to show you just how hard this whole writing thing is. Even with an established author and an Instagram influencer working together as a team, still, we are up against market forces that make this red rope very thick and high.

Selling a book on a proposal is not a straightforward process, nor is it easy—no part of writing ever is. And of course the process becomes more complicated when you have two authors, instead of one, and when you are beholden to truth-telling, as we are in memoir. For you novelists out there, take heart in the fact that you are always free to bend the rules, to play with physics, to sculpt the content of your writing to the will of your imagination. In memoir, we are not. We are limited to the truth, and how we get to play is by deciding how to organize the revelations of those truths.

But even with impeccable structuring and plotting and contacts to beat the band, selling a book on proposal is harder than a lot of people make it out to be. Even at the published level with five books behind me—getting a nonfiction book deal is never a given. I hope that the disclosure of this information is somehow inspiring and emboldening to you instead of depressing? Savanah and I aren’t giving up, and you shouldn’t either.

That being said, if you want to protect yourself against the market forces or at least educate yourself on them, I have two online classes—one on Memoir Writing and one on Book Proposal writing that can help you to judge the viability of your book project before you start querying or submitting it to editors. The hyperlinks above will give you a special discount to the class.

Thanks for being here! And thank you for your support and enthusiasm toward The Savanah Project. If you’ve had experience refining a life story that had too many ups and downs or you’ve been hit with the “this needs a Happy Ending” verdict yourself, please share your experience with us in the comments! As usual, if you don’t have anything nice to say, there’s no compelling reason to share it. Let’s keep each other feeling supported and seen in this community of ours.

This just in! I have three one-month subscriptions to

“Publishing Confidential” Substack I’d love to gift. Reply with your email address below if you’d like one— the first three people to respond win!Courtney

I am not available to co-author book proposals with other writers at this time. If you are looking for someone to help you with book proposal writing, send an email to me at thequerydoula (at) gmail (dot) com and the out of office will give you a list of developmental editors that might be right for you. I also have an online book proposal writing class here.

This is an affiliate link, as is the link for Lauren Hough’s memoir.

The best email is thequerydoula@gmail.com

Even if there aren't overt faith references, a book like this with forgiveness as a theme might interest Nashville-based Big Five imprints who primarily publish in the Christian category but also look for projects that would have crossover appeal into the general market. I know Onsite is faith-adjacent, so that may or may not be a path forward depending on how you and Savanah would feel about a primarily Christian publisher. Just a thought! And regarding Option 5, I think Savanah's story would have a lot of alignment with the kinds of stories and features in Magnolia Journal and on Magnolia Network. I *think* Carly Watters represents the former editor for Magnolia Journal so that could be an avenue to explore.

There's a lot to unpack here, but I'm not sure there's a great option other than the patience you mentioned. The fact that the "happy" ending isn't there feels like the Big Five isn't really plugged in to the real world which is a huge loss for readers. And who knows, maybe Tennessee IS the happy ending for Savanah right now. I feel like this is a project you put aside but don't abandon (because as you mention in Option 1 - you can't risk alienating publishers who might buy your novel in '24). Memoir readers might actually be taken with this book (and stongly relate to the reality that all things don't end "happily") but maybe it's a perspective shift on what "happily" actually is and publishers are too afraid to go out on a limb for that. At any rate, thanks for this incredibly insightful update. I hope her story still makes it into the wider world at some point (even if it is memoir-in-essays, which sounds very interesting).